Women in the ancient Greek world had few rights in comparison to male citizens. Unable to vote, own land, or inherit, a woman's place was in the home and her purpose in life was the rearing of children. That is a general description and when considering Greek women one should remember our sources are incomplete and not always unbiased.

Unfortunately, information regarding specific city-states is often lacking regarding women and is almost always from male authors. Only in Athens can their status and role be described in any great detail. Neither are we sure of the practical and everyday application of the rules and laws that have survived from antiquity. We do know that Spartan women were treated somewhat differently than in other states. For example, they had to do physical training like men, were permitted to own land, and could drink wine.

There were also categories of women which are less well-documented than others such as professional women who worked in shops and as prostitutes and courtesans; the social rules and customs applied to them are even more vague than for the female members of citizen families. Finally, in contrast to the lot of most women, some exceptionally and exceptional, rose above the limitations of Greek society and gained lasting acclaim as poets (Sappho of Lesbos), philosophers (Arete of Cyrene), leaders (Gorgo of Sparta and Aspasia of Athens), and physicians (Agnodice of Athens).

Women in Mythology

Considering their limited role in actual society there is a surprisingly strong cast of female characters in Greek religion and mythology. Athena, the goddess of wisdom and patron of Athens stands out as a powerful figure blessed with intelligence, courage and honour. Again common to most ancient cultures where agriculture was crucial to the community, female fertility goddesses were extremely important and particularly venerated - Demeter and Persephone being the most revered for the Greeks.

As in other ancient male-dominated literature, women are often cast as troublemakers, from jealous Hera to Aphrodite employing her charms to make men lose their wits. Myths and literature abound with female characters trying their best to derail the plans of male heroes, from the supreme witch Medea to the deadly, if lovely, Sirens. They can also be represented as ruled only by wild passion and ecstatic emotion such as the Maenads. In contrast, the ideal chaste woman loyal to her absent husband is epitomised by Penelope in Homer's Odyssey. The Muses are another positive representation, celebrated not only for their physical beauty but also their wide-ranging skills in the arts. Whether these fictional characters had any bearing on the role of women in real life is an open question, as is the more intriguing one of what did Greek women themselves think of such male-created role-models? Perhaps we will never know.

Girls

As in many other male-dominated and agrarian cultures, female babies were at a much higher risk of being abandoned at birth by their parents than male offspring. Children of citizens attended schools where the curriculum covered reading, writing, and mathematics. After these basics were mastered, studies turned to literature (for example, Homer), poetry, and music (especially the lyre). Athletics was also an essential element in a young person's education. Girls were educated in a similar manner to boys but with a greater emphasis on dancing, gymnastics, and musical accomplishment which could be shown off in musical competitions and at religious festivals and ceremonies. The ultimate goal of a girl's education was to prepare her for her role in rearing a family and not directly to stimulate intellectual development.

An important part of a girl's upbringing involved pederasty (it was not only practised by mature males and boys). This was a relationship between an adult and an adolescent which included sexual relations but in addition to a physical relationship, the older partner acted as a mentor to the youth and educated them through the elder's worldly and practical experience.

Young Women

Young women were expected to marry as a virgin, and marriage was usually organised by their father, who chose the husband and accepted from him a dowry. If a woman had no father, then her interests (marriage prospects and property management) were looked after by a guardian (kyrios or kurios), perhaps an uncle or another male relative. Married at the typical age of 13 or 14, love had little to do with the matching of husband and wife (damar). Of course, love may have developed between the couple, but the best that might be hoped for was philia - a general friendship/love sentiment; eros, the love of desire, was often sought elsewhere by the husband. All women were expected to marry, there was no provision and no role in Greek society for single mature females.

Married Women

In the family home, women were expected to rear children and manage the daily requirements of the household. They had the help of slaves if the husband could afford them. Contact with non-family males was discouraged and women largely occupied their time with indoor activities such as wool-work and weaving. They could go out and visit the homes of friends and were able to participate in public religious ceremonies and festivals. Whether women could attend theatre performances or not is still disputed amongst scholars. More clear is that women could not attend public assemblies, vote, or hold public office. Even a woman's name was not to be mentioned in public – for good reasons or bad.

If a woman's father died, she usually inherited nothing if she had any brothers. If she were a single child, then either her guardian or husband, when married, took control of the inheritance. In some cases when a single female inherited her father's estate, she was obliged to marry her nearest male relative, typically an uncle. Females could inherit from the death of other male relatives, providing there was no male relative in line. Women did have some personal property, typically acquired as gifts from family members, which was usually in the form of clothes and jewellery. Women could not make a will and, on death, all of their property would go to their husband.

Marriages could be ended on three grounds. The first and most common was repudiation by the husband (apopempsis or ekpempsis). No reason was necessary, only the return of the dowry was expected. The second termination cause was the wife leaving the family home (apoleipsis), and in this case, the woman's new guardian was required to act as her legal representative. This was, however, a rare occurrence, and the woman's reputation in society was damaged as a result. The third ground for termination was when the bride's father asked for his daughter back (aphairesis), probably to offer her to another man with a more attractive dowry. This last option was only possible, however, if the wife had not had children. If a woman was left a widow, she was required to marry a close male relative in order to ensure property stayed within the family.

Other Roles

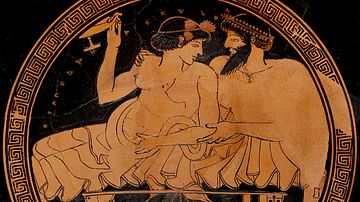

Women, of course, were also present in the various other non-citizen classes. As slaves, they would have performed all manner of duties and they would also have worked in businesses such as shops and bakeries. The group for which we have most information is that of sex-workers. Women were here divided into two categories. The first and perhaps most common was the brothel prostitute (pornē). The second type was the higher-class prostitute (hetaira). These latter women were educated in music (especially the flute) and culture and often formed lasting relationships with married men. It was also this class of women that entertained men (in every sense) at the celebrated symposium, the private drinking party for male guests only.

Finally, some women participated in cults and performed as priestesses to certain female deities (Demeter and Aphrodite especially) and also Dionysos. Priestesses, unlike their male counterparts, did have the added restriction that they were often, but not always, selected because they were virgins or beyond menopause. Worshippers, on the other hand, could be both sexes, and those rituals with restrictions could exclude either men or women. The Thesmophoria fertility festival was the most widespread such event and was only attended by married women. Each year in Athens, four young women were selected to serve the priestess of Athena Polias and weave the sacred peplos robe which would adorn the cult statue of the goddess. Perhaps the most famous female religious role was the aged Pythia oracle at Delphi who interpreted the proclamations of Apollo.