Despite allegedly founding Rome and being hailed a hero, Romulus’ legacy is complex and his biography is even disturbing at times. He was supposedly guilty of committing many terrible deeds that still make readers recoil, but according to legend, his transgressions often led to positive outcomes – at least from the Romans’ point of view. Thanks to his efforts' results, the Romans largely celebrated their fabled founder, and it seems that they recognized valuable lessons hiding within his biography: greatness sometimes stems from disgrace, and the path to redemption is often close at hand.

Lineage & Birth

According to Rome's canonical foundation myth, Romulus was born sometime in the 700s BCE. His parents were supposedly a priestess – called Rhea Silvia – and the god of war Mars, which provided Romulus with a pedigree second to few in the ancient world. To some, this might have intimated that he would enjoy a lifetime of opulence, without serious challenges, and he would be a paragon of morality. On the contrary, Romulus was fated for a life marked by instances of ignominy and egregious misdeeds.

Romulus’ maternal grandfather was known as Numitor, and he was king of Alba Longa, which was an influential settlement nestled in the Alban Hills of central Italy. Ancient historians traced its foundation to none other than one of Aeneas’ descendants. However, sometime after Numitor ascended to the throne, his jealous brother Amulius conspired to overthrow Numitor’s rule, and somehow, he succeeded in his endeavors and became Alba Longa’s king. In order to further secure his grasp on power, Amulius treacherously ordered the murder of Numitor’s son, Aegestus, and forced Numitor’s daughter, Rhea Silvia, to become a priestess to Vesta who was the goddess of the hearth. Since such priestesses were required to be chaste during their tenure under the pain of death, Amulius assumed that Rhea would not mother any potential rivals to the throne. But as the Romulus tale goes, Mars ravaged her one day. This led to her pregnancy, and she later gave birth to twins: Romulus and Remus.

Even though Rhea attempted to conceal the truth, Amulius learned of Rhea’s pregnancy, and shortly after Romulus and Remus’ births, the rogue, tyrannical king of Alba Longa condemned the infants to death by drowning. Yet by a dispensation of fate, they survived. Initially, a wolf named Lupa allegedly protected them until a shepherd called Faustulus rescued the boys and raised them as his own children. Around 18 years or so after their abandonment, Romulus and Remus returned to Alba Longa, led an armed revolt, and freed the Alba Longans from the despot's control, killing Amulius and placing the gentle Numitor back on the throne.

At no fault of his own, Romulus' early life had been tainted by a disgraceful act – attempted infanticide – but he overcame this impediment and displayed his potential value. Indeed, he survived a close call with death, restored proper rule within Alba Longa, and delivered what the ancients felt was appropriate justice to his enemies. Despite overcoming these challenges and demonstrating some admirable qualities, Romulus proved to be his legacy's own worst enemy and revealed that he was a seriously flawed character.

The Foundation of Rome

Not long after deposing Amulius, Romulus and his twin brother pondered their futures. They were ambitious but realized that they could aspire to be little more than respected princes of Alba Longa so long as Numitor was alive. So, they purportedly resolved to found a city of their own nearby, but they clashed over a few issues, including its specific location and who would be its king. They ultimately decided to leave the decision up to the gods by way of an augury contest in which they would scan the sky for vultures, and whoever observed the more favorable sign would become king and determine where they would build their city.

Romulus was worried that he may lose the contest, and he decided to cheat to better his odds of being victorious. To this end, he dispatched a missive falsely informing his brother that he had witnessed a sign, but the message arrived too late. Remus had already watched six vultures fly over his location, which he took as proof that the gods favored him. Only after this did Romulus actually see 12 vultures soaring over his viewing station. Remus became aware of Romulus’ duplicity, which naturally angered him, and the two subsequently argued over which sign was more favorable – the first one witnessed or the larger number of vultures. This disagreement drove a dangerous wedge between the stubborn twins.

Sometime later, during one of Romulus’ construction projects, Remus and his friends decided to inspect their workings. Remus was unimpressed, and he belittled the fortifications, even though this certainly offended Romulus and his faction. Perhaps to prove his point, Remus even vaulted over the barricade, which seemed to display its shortcomings. Upon landing, in a fit of anger, Romulus – or one of his deputies – drove a pickax into Remus’ head, killing him. The act, according to the historian Orosius, "ruined the reputation of [Romulus'] reign," and the ancient poet Horace believed that this dispute set the stage for Rome’s later struggles (Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, 2.4). In fact, he wrote:

What hounds the Romans is bitter fate and the crime of a brother’s murder, ever since the blood of innocent Remus flowed into the earth, a curse to his descendants (Horace, Epodes, 7.17–20).

Romulus had much for which to be repentant. He had blatantly cheated in a sacred augury contest, and Remus’ murder was absolutely despicable. To some Romans, it was even unforgivable. "No one shall acquit Romulus of unreasoning anger or hasty and senseless wrath in dealing with his brother," Plutarch remarked (Plutarch, Comparison of Theseus and Romulus, 3.1). "There could have been no good reason for his flying into such a passion" (Plutarch, Comparison of Theseus and Romulus, 3.2). Nevertheless, Romulus managed to achieve some level of redemption due to his subsequent endeavors. Romulus allegedly chose Rome's location (atop the Palatine Hill), which proved to be a wise choice; created beloved religious, social, and civic rules; and became Rome's first king.

Romulus' power grab was necessary according to some. The ancient writer Florus wrote: "For where could greater boldness be found than in Romulus? Such a man was needed to seize the kingship" (Florus, The Epitome of Roman History, 1.8.2). Similarly, the Roman jurist Cicero (106-43 BCE) praised Romulus for choosing Rome's site, which he thought allowed Rome to thrive, and for creating the "admirable foundation-stones of the state" (Cicero, On the Republic, 2.17). By that, Cicero meant the Roman Senate and the use of augury.

Plutarch commended Romulus for rising from his lowly station and wrote:

But Romulus has, in the first place, this great superiority, that he rose to eminence from the smallest beginnings. For he and his brother were reputed to be slaves and sons of swineherds, and yet they not only made themselves free, but freed first almost all the Latins, enjoying at one and the same time such most honourable titles as slayers of their foes, saviours of their kindred and friends, kings of races and peoples, founders of cities (Plutarch, Comparison of Theseus and Romulus, 4.1).

The Sabine Women

Despite bolstering his legacy with these laudable actions, Romulus purportedly exhibited his penchant for outrageous misbehavior again. Not long after Rome’s founding, Romulus grew concerned about his nascent settlement’s future. He had founded it along with many shepherds and outcasts from Alba Longa who were predominantly males. He also created a policy of providing asylum to those who wished to become Roman citizens – even if they were fugitives and debtors from other cities. This helped grow Rome’s population, but the immigrants were almost exclusively men. Without a considerable influx of females within Rome, the city might be doomed in a generation if not sooner. After all, without them, there could be no procreation to create a new generation of Romans.

Vexed by Rome's lack of women, the Roman king plotted with his confidantes. After piecing together a deceptive scheme, Romulus invited the neighboring communities to attend a grand festival – possibly dedicated to the god Consus. As such, people from around central Italy naively entered Rome and were prepared to enjoy the revelry, the athletic contests, and great spectacles.

The climax of the festival was a horse race. When it was underway and the foreign audience was focused on the sporting event, Romulus gave the signal for his subordinates to initiate their devious plan. Then sword-wielding Romans dashed into the crowd, kidnapped as many as 683 virgins, and forced them to marry the Roman bachelors. Orosius understandably denounced the ploy as "shameless." He wrote:

[Romulus’] action in holding the Sabine women, whom he had enticed by offering them a treaty and by inviting them to a celebration of games, was as wicked as was his dishonesty in seizing them in the beginning (Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, 2.4).

According to legend, however, the marriages resulted in sincerely loving unions, but they also sparked numerous wars. Romulus battled and defeated the armies of Caenina, Antemnae, and Crustumerium. He also prosecuted a defensive war against the Sabines who were led by King Titus Tatius, but it was ultimately fought to a draw. Faced with the reality of a deadly, protracted war, the two leaders resolved to join together and rule Rome as co-monarchs. Because of all of this, once again, Romulus was able to recover some of his reputation – at least in the Romans' eyes. That is because the forced marriages were fruitful – leading to many births – and after a series of related military conflicts, Rome rapidly grew in size, population, and might.

Later Years & Death

As the years passed, Romulus allegedly also waged successful wars on Cameria, Fidenae, and the mighty city of Veii, and he planted colonies and admitted many defeated peoples into Rome as citizens – as his tax base and number of men-at-arms surged. The ancient writer Tacitus (c. 56 - c. 118 CE) even applauded Romulus’ actions and said: "Romulus, on the other hand, was so wise that he fought as enemies and then hailed as fellow-citizens several nations on the very same day" (Tacitus, The Annals, 11.24).

Due to Romulus’ efforts, Rome was temporarily secured from outside attacks, but not all was well within Rome. By some accounts, Romulus increasingly grew tyrannical and abandoned many governmental forms that he had created. Indeed, he often acted without the Senate's or people's consent, he directed his attendants to beat the citizens who displeased him, and he ordered the grisly deaths of others who were subsequently flung from the Tarpeian Rock – doubtlessly before a terrified and captive audience.

All of this angered his subjects, and depending on which tradition you read, Romulus either miraculously ascended into the heavens to live with his godly father Mars or was murdered. Some ancient authors understandably rejected his supernatural apotheosis and instead asserted that due to Romulus’ oppressive rule, his senators killed him in secret, cut his body into tiny bits, and then hid the remains. Afterward, they informed the Roman populace that they had seen Romulus being called to the heavens.

Whatever the case, the Roman founder once again somehow managed to obtain a degree of redemption – possibly due to the foundations that he established, the growth that he had spurred, and for building Rome into a military powerhouse. In fact, he became recognized as the god Quirinus – the god of the Roman state – and eventually enjoyed a temple worthy of his honor.

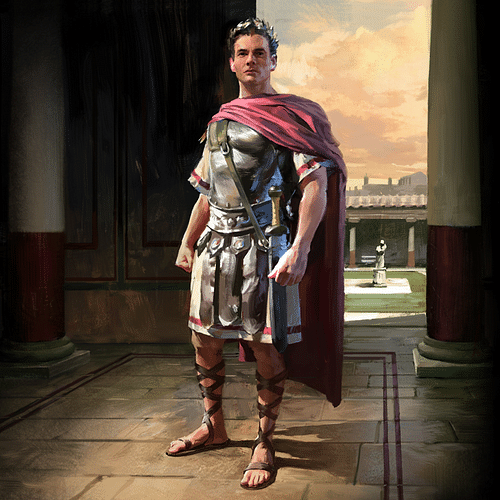

Romulus' Image

Despite the ancients acknowledging Romulus’ many misdeeds, even long after his death, the Romans largely viewed him as a laudable hero. His name was attached to such power and legitimacy that many yearned to be called another Romulus or a founder of Rome. During the Roman Republic, the celebrated generals Marcus Furius Camillus (c. 446-365 BCE) and Gaius Marius (c. 157-86 BCE) earned the proud honor of being hailed as founders of Rome. While they did not physically establish Rome, many felt that their efforts ushered in a rebirth of the republican city-state and that their great contributions compared to Romulus’. This was a great privilege that many desired.

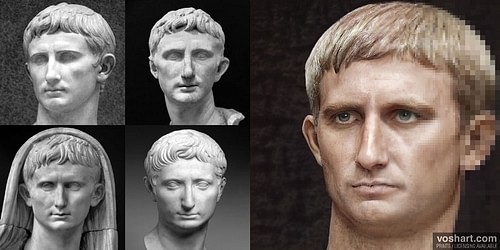

There were ancient historians who believed that Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) considered being closely associated with Romulus, and some even called him 'a Romulus', given that he had provided some level of stability in Rome and expanded its borders. Similarly, the first Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) weighed adopting Romulus’ name after someone suggested it. He ultimately opted against doing so, which was probably a wise decision, considering that the Romans of this era loathed the idea of being ruled by a king.

Nevertheless, perhaps in an effort to intertwine the greatness of Romulus and Augustus, at the emperor’s funeral, funerary participants displayed images of Romulus – all of which demonstrates the high regard that many had for Romulus. Other Romans were far less subtle in their attempts to be associated with Romulus’ greatness. In fact, an untold number of Roman parents even named their children Romulus.

However, Romulus’ legendary misbehavior seemed to give others license to act inappropriately. In one such example, while attending the wedding of Gaius Calpurnius Piso and Livia Orestilla, the troubled emperor Caligula (r. 37-41 CE) decided to abscond with Piso’s new bride. Indeed, he stole her away and married her. Caligula later declared that he had obtained a wife through the same method that Romulus and his subjects had acquired their brides: kidnapping.

The truth is that Romulus was an absolute menace in many ways. Yet his biography taught the Romans that few people have unblemished careers, but their misdeeds do not necessarily invalidate their accomplishments. In Romulus' case, his supposed life demonstrated to the Romans that heroism and glory can sometimes be traced to those who are critically defective. While everyone should aspire to be a better person than Romulus, partially thanks to him – the Romans believed – Rome had been founded, grew into a massively successful empire, and in many ways, thrived for over a thousand years.