Samudragupta (r. 335/350 - 370/380 CE) was the first significant ruler of the Gupta Dynasty. Having come to the throne, he decided to extend the boundaries of his empire to cover the multiple kingdoms and republics that existed outside its pale. Known as the 'Napoleon of India' for his conquests, he was also a man of many talents and laid a firm foundation for the empire. The rise of the Gupta Empire and the beginning of its prosperity are attributed to him, his military conquests and policies.

Succession

Samudragupta succeeded his father Chandragupta I (r. 319 – 335 CE). Some historians, however, state that he was preceded by Kachagupta or Kacha who was Chandragupta I's eldest son. Kacha's identity is yet to be established, as only some coins bearing the name have been found and no other evidence of his rule has been discovered so far. The fact that Chandragupta I actually nominated Samudragupta to the throne shows that he was not his eldest son. Therefore, it could be possible that the historians are justified in saying that Kacha was the eldest son who succeeded his father as according to the ancient Indian custom of male primogeniture (his father's own wishes on the matter notwithstanding). Thus, Chandragupta could only nominate his younger son based on his abilities but was not able to actually make him king.

It is not clear as to whether Samudragupta opposed him or that Kachagupta's end was natural and he was succeeded by his sibling because he had no other heir. As to why Samudragupta opposed Kachagupta, if he did so at all, no information is available. What is known is that he was ultimately able to claim the throne.

Details of Kachagupta's reign are hardly mentioned in the historical evidence existing for the Gupta period, and hence most historians place Samudragupta as the successor of Chandragupta I, stating that Kacha was none other than Samudragupta himself; “Perhaps Kacha was the original or personal name, and the appellation Samudragupta was adopted in allusion to his conquests” (Tripathi, 240). Historian R.K. Mukherjee correctly explains that the title Samudragupta “means that he was 'protected by the sea' up to which his dominion was extended” (19). Referring to Samudragupta's accession, historian H.C. Raychaudhuri says that “the prince was selected from among his sons by Chandra Gupta I as best fitted to succeed him. The new monarch may have been known also as Kacha” (447). The grounds for such an assertion is an epithet implying “uprooter of all kings” used for Kacha in his coins, which was used only for Samudragupta as no other Gupta emperor ever made such extensive conquests. Had Kacha existed before Samudragupta and made such conquests, there would have been no need for the latter to make them! Kacha would have thus been included in the official Gupta records in glorified terms as well, which is not the case. As regarding Kacha's coins, “the attribution of the coins bearing the name Kacha to Samudra Gupta may be accepted” (Raychaudhuri, 463).

Though not validated by historical sources, another theory maintains that Chandragupta I managed to override the male primogeniture law and made his favourite Samudragupta the king. Enraged at his supersession as the eldest son, Kacha never reconciled with his brother and rebelled against him for the throne but was defeated.

Conquests: The 'Indian Napoleon'

Samudragupta is known chiefly for his numerous military campaigns. The British historian Vincent Smith (1848 – 1920 CE) was the first to dub him as 'the Indian Napoleon'. His many conquests have been alluded to in the Allahabad pillar inscription, composed by a high-ranking official named Harishena, who was also a skilled author and poet. This inscription is the chief (if not the only) source for his campaigns and conquests, and hence is regarded as crucial for studying Samudragupta's reign, “if we believe the eulogistic inscription from Allahabad, it would appear that Samudragupta never knew any defeat, and because of his bravery and generalship he is called the Napoleon of India” (Sharma, 153).

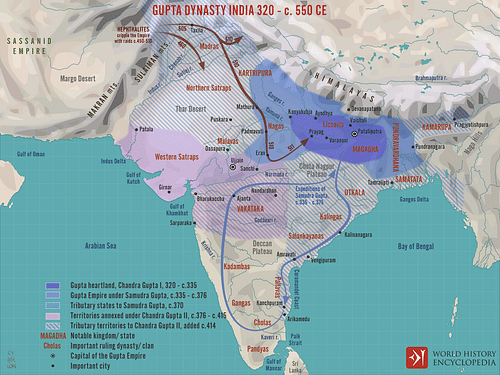

Initially, Samudragupta concentrated on the areas bordering the existing Gupta Empire at the time. According to lines 14 - 21 of this inscription, he attacked the ruler of the upper Ganga valley and destroyed many other kings, notably Rudradeva, Matila, Nagadatta, Chandravarman, Ganapatinaga, Nagasena, Achyuta, Nandin and Balavarman. The identities of some of these rulers and the kingdoms they ruled are still not clear. It has been surmised, however, that most of these kingdoms lay in the state of present-day Uttar Pradesh and were annexed to the empire.

Violent destruction was not the only means adopted by Samudragupta. He made the kings of the forest states (atavika rajya) in central India his servants. For some other kings, it was considered sufficient if they paid tribute and gave obeisance to the Gupta emperor. Line 22 of the Allahabad inscription gives the details. These kings were ruling the areas of Samatata (present-day Bengal state), Devaka and Kamarupa (present-day Assam state), Nepala (present-day country of Nepal) and Kartripura (parts of present-day Punjab and Uttarakhand states).

The chiefs of various republics too were added to this list of kings. These republics included those of the Malavas, Arjunayanas, Yaudheyas, Madrakas, Abhiras, Prarjunas, Sanakanikas, Kakas and Kharaparikas. These covered many areas of north-west India, including parts of the present-day states of Rajasthan and Punjab.

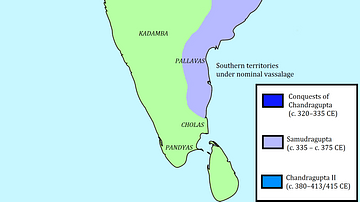

Samudragupta also captured and released several other kings, whose names and kingdoms are given in lines 19 and 20. These included kings from the present-day states of Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana and the eastern and south-eastern coasts of India:

- Mahendra of Kosala

- Vyaghraraja of Mahakantara

- Mantaraja of Kairala or Kaurala

- Mahendra of Pishtapura

- Svamidatta of Kottura

- Damana of Erandapalla

- Vishnugopa of Kanchi

- Nilaraja of Avamukta

- Hastivarman of Vengi

- Ugrasena of Palakka

- Kubera of Devarashtra

- Dhananjaya of Kusthalapura

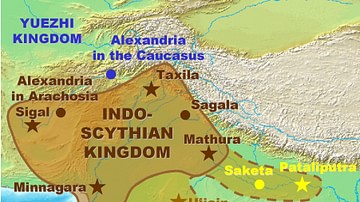

Some other subdued kings were given the task of rendering all kinds of service to the emperor, using the official Gupta seal and entering into matrimonial alliance with the imperial dynasty if they so chose. These included the Kushana rulers and the Scythians (Shakas and Murundas) as well as the King of Sri Lanka.

Conquests: Strategy

Samudragupta's strategy was guided by the prevailing political and economic conditions. He realized that he could not control directly a vast empire from his capital and hence focused on annexing those kingdoms which lay on his borders. For the rest, only an acceptance of suzerainty was needed while their own kings would be left to deal with issues of governance and administration. At the same time, being subordinate, they would not create challenges for the Guptas. The geographical location of the kings thus determined what category they would be placed in. As historian Raychaudhuri puts it, “In the north he played the part of a digvijayi or “conqueror of the quarters,” of the Early Magadhan type. But in the south he followed the Epic and Kautilyan ideal of a dharmavijayi or “righteous conqueror,” i.e., he defeated the kings but did not annex their territory. He may have realised the futility of attempting to maintain effective control over these distant regions in the south from his remote base in the north-east of India” (Raychaudhuri, 451).

Therefore, unlike the Mauryas (4th century BCE to 2nd century BCE), the Gupta empire under Samudragupta did not directly control many of the constituents of the empire. Samudragupta, thus, despite his conquests, did not create an all-India empire. Using his military power, he instead built up the political machinery in such a way that the Gupta suzerainty and paramountcy came to be acknowledged over most of the subcontinent and many kingdoms and republics regarded themselves as subordinate to the Gupta emperor.

Given the time, with feudalism making rapid inroads, this was probably the best way to create a widespread empire. Direct control and a centralized system as under the Mauryas were no longer tenable. In the changed circumstances, the Guptas could not hope to exercise monopolistic control over the economy and hence would not have had the vast resources necessary to run a bureaucratic empire with a vast military. The best idea, then, was to build a military mighty enough to cow down the enemy and keep him cowed. Able to garner suzerainty in such a manner, Samudragupta believed he could create and keep the peace necessary for his empire to prosper.

Extent of the Empire

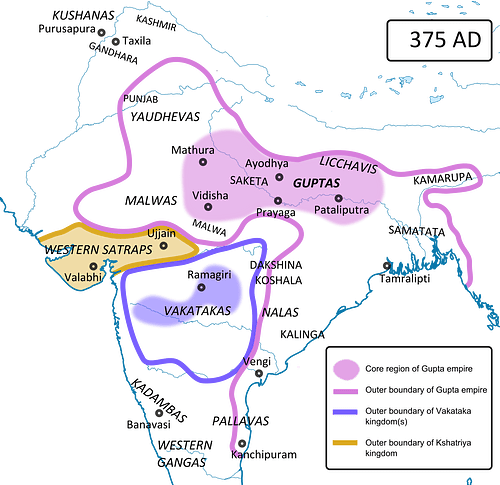

At his succession, Samudragupta seems to have possessed an empire that included Magadha and its adjoining areas from the present-day states of Uttar Pradesh and Bengal. In the north, the boundaries of this empire stretched to the Himalayan foothills. His annexation of the territories of some of the defeated kings led to the extension of the borders of the Gupta Empire. Thus, the Ganga-Yamuna valley including the cities of Mathura in the east and Padmavati in the west came to be included in the Gupta Empire.

Most of northern India barring Kashmir, western Punjab, most of Rajasthan, Sindh (now in Pakistan) and Gujarat became part of his empire, which also came to include the highlands of central India and many areas on the eastern coast. The borders of the Gupta Empire were ringed by kingdoms which were subordinated to Gupta rule and recognized its primacy. The king of Sri Lanka and the Kushana and Scythian kings acknowledged his suzerainty. The kings of southern India, though not a part of the empire directly or indirectly, had been humbled (or cowed) through the military conquests and hence were seen as not posing any kind of threat to the peace and prosperity of the empire.

Warrior & Commander

Samudragupta and the princes were supposed to be matchless warriors themselves, like his son prince Chandragupta II. Samudragupta took a personal interest in all his wars and campaigns which were not left to the discretion of his ministers and generals. He personally took part in the battles, often leading from the front. “All his conquests the king achieved by his personal leadership and fighting in the front-line as a soldier (samgrameshu-svabhuja-vijitah)” (Mookerjee, 39). The inscriptions state that he relied a lot on his personal might and that he was a fearless fighter who had fought a hundred battles (samarashata) which left on his body their scars (vrana) as marks of decoration (shobha) and glowing beauty (kanti), caused by different kinds of weapons of war.

Patron of Arts

Samudragupta was as devoted to the arts of peace as to war. He was a great musician and played the vina, an Indian stringed instrument resembling the lyre or lute, with great aplomb. He was a highly intellectual person and an accomplished poet. He was always depicted as an able and compassionate ruler, who cared a lot for the welfare of his subjects, particularly the poor and the destitute. He granted permission to the Sri Lankan king to build a Buddhist monastery and rest house for Sri Lankan pilgrims at Bodhgaya.

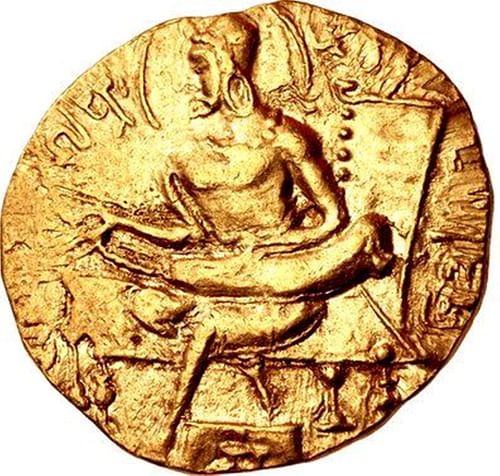

Coins

A lot of information about Samudragupta both as a king and a person has been made available through his gold coins. His coins represent him both as a warrior and a peace-loving artist, with relevant suitable titles. They are classified according to the object or weapon the emperor is holding i.e., a battle-axe, vina or bow, or the animal represented on the coin, i.e. a tiger. “The archer and battleaxe coin types of Samudragupta predictably advertise his physical prowess, while the lyrist type, which shows him playing the vina, represents a completely different aspect of his personality” (Singh, 55).

The various titles used by the monarch have become known through the coins. Thus parakramanka (“marked with prowess”) is found on the reverse of coins of the standard type, apratiratha (“unparalleled chariot warrior” or “great warrior”) on the archer type, kritantiparashu (“axe of death”) on the battle-axe type and the vyaghra-parakrama (“like a tiger in strength”) on the tiger type of coins. He is also depicted as having carried out the ashvamedha sacrifice, which was traditionally carried out by ancient Indian kings to display their prowess and conquests, and thus their supremacy over other kings.

The obverse side on the standard type bears witness to his extensive conquests through the legend samara-shata-vitata-vijayo jita-aripuranto-divam-jayati or “The conqueror of the unconquered fortresses of his enemies, whose victory was spread in hundreds of battles, conquers heaven”.

Reorganization of the Gupta Military

Since the military played a huge role during Samudragupta's reign, it is quite probable that the emperor took stern measures to increase its size and efficiency. Increased contact with the Scythians (Shakas and Kushanas) in India caused many of their military equipment and clothing to be adopted by the Guptas; “it was the Kushan army, well clad and equipped, that became the prototype on which the new military uniform of the Guptas was based” (Alkazi, 99). Samudragupta is seen wearing a Scythian-type costume on his coins.

The soldiers mostly abandoned the complex turban that had been usually worn earlier and wore their hair loose or tied back with a fillet or skull caps and simple turbans, with tunics, crossed belts on the bare chest or a short, tight-fitting blouse. This was accompanied by a typically Indian loose lower garment worn in the drawer style or Scythian-inspired trousers with high boots, helmets and caps.

There was even a kind of camouflage clothing made by applying tie-dye techniques to cloth. The cavalrymen wore coats and trousers, which were often very colourful and gaily decorated. The elephant warriors were dressed in decorated blouses and striped drawers. The elites commanding the army or other officials, along with coats and trousers, wore armour (especially of metal). Other classes of crack troops were similarly well-furnished.

Shields were rectangular or curved and often made from rhinoceros hide in checked designs. Many kinds of weapons such as curved swords, bows and arrows, javelins, lances, axes, pikes, clubs and maces were used.

In ancient India, initially, the army was fourfold (chaturanga), consisting of infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots. By the time of the Guptas, the chariots were going into disuse, and the onus was falling on the other three arms. Each arm had its own head (or commander). The chief of the army was called as the baladhikarananika or baladhikarana. The head of the infantry and the cavalry was the bhatashvapati. The head of the elephants was known as the mahapilupati. The army consisted of the standing army of the state (maula), mercenaries (bhrita), allied forces (mitra) and those furnished by corporate guilds (shreni).

Legacy

Through his carefully guided strategy for conquests, Samudragupta created a model for conquest and governance well suited to the changed political and economic conditions of ancient India in the 4th century CE. The large number of gold coins that he issued bear witness to the prosperity of the Gupta empire in his time. “As a ruler, he was known for his vigorous and resolute government” (Mookerjee, 38). Despite his wars and conquests, Samudragupta thus left no other aspect of governance unattended.

According to the evidence of the coins, he was succeeded by his son Ramagupta, who, being weak and immoral, was deposed (and perhaps killed) by his brother who became famous as Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (before 381 CE- 413-14 CE). He proved to be an able ruler and conqueror and was the next well-known ruler of the dynasty with many achievements to his credit. He carried on the legacy of Samudragupta; not only he but the Gupta empire itself owed much to the efforts of Samudragupta in building and sustaining an extensive empire that carved out an impressive place for itself in history.