The Roanoke Colony was England's first colony in North America, located in what is today North Carolina, USA. Established in 1585 CE, abandoned and then resettled in 1587 CE, the colonists had little regard for their new environment and were soon in conflict with the peoples who already inhabited the region. Doomed to failure, this early colonial project lacked adequate planning and logistical support. Further, an attack on a Native American village and murder of its chief would permanently sour relations for those that followed. The second group of Roanoke colonists were left to their own devices and when hopelessly delayed resupply ships did finally arrive, no trace of them could be found except one word carved on a tree trunk: 'Croatoan'. The most likely explanation for the fate of the colonists is that they were killed by the Roanoke Indians keen to free their island of this nuisance from the Old World.

1584 CE: First Contact

England had been rather left behind in the European race to colonise newly discovered parts of the world. While the Spanish were busy pillaging the Americas and the Portuguese had long been trading in West Africa, Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE) was content to fund privateers who robbed Spanish treasure ships taking loot from the Americas. In March 1584 CE, however, she finally agreed to attempt a settlement of colonists in the area Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618 CE) would name in her honour, Virginia. This region, today's North Carolina in the USA, was visited by Englishmen in the summer of 1584 CE as Raleigh was eager to exercise Elizabeth's six-year patent to establish a New World colony where the settlers would have equal rights to any citizen in England.

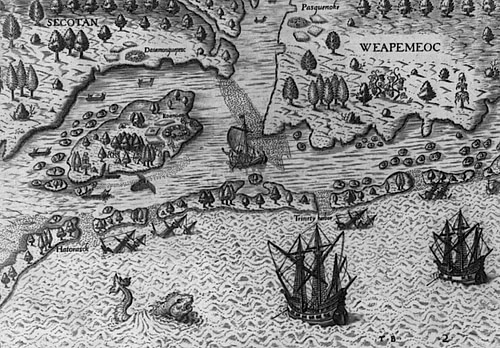

The 1584 CE expedition, often called the Amadas-Barlowe Expedition after its two leaders, explored the region and made contact with Indians whose main settlement was on Roanoke Island. Relations were friendly and meat and fish were acquired in exchange for cloth and wine. The local chief, one Wingina, even entertained the Europeans with a great feast. Two Roanoke Indians then volunteered to accompany the explorers back to England: Manteo and Wanchese. Back home, Barlowe described Virginia as a land of plenty with peaceful natives and he showed off the skins and pearls he had acquired via trade. It seemed this was indeed a spot worth further investigation and a good candidate for England to establish its first permanent colony.

1585 CE: The First Settlement

Once again, Raleigh was the mastermind behind the project to extract the riches everyone hoped the new land could provide. Unfortunately, in the typical optimism of the period, the Europeans had not much idea of the challenges involved and not much concern at all for the peoples who already inhabited the region. Both of these mistakes would combine and lead to ultimate failure in England's first colonization project. Along the way, there was adventure, hardship, death, and some mystery.

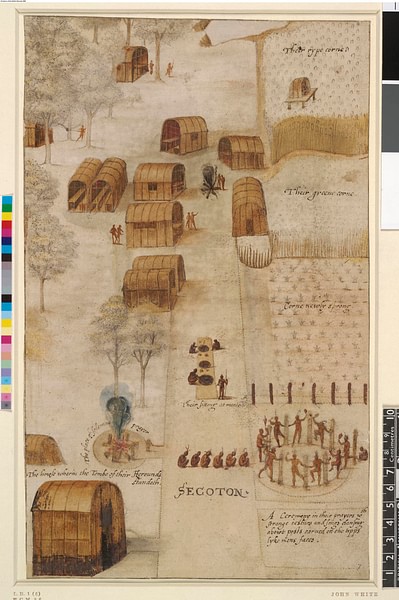

In 1585 CE, then, the adventurer Richard Grenville (1542-1591 CE) was given command of a small fleet which sailed to North America carrying a group of colonists. Elizabeth did not give any financial backing despite the flattery of Raleigh's name choice, but she did provide the expedition with the 160-ton ship Tyger. Grenville left Plymouth on 9 April 1585 CE with his fleet of five ships, of which Tyger was the largest. The crew included a young Thomas Cavendish (1560-1592 CE) who would later circumnavigate the globe in 1586-88 CE. Another famous name was John White (d. 1593 CE), the celebrated cartographer and artist who mapped and captured the sights of this corner of the New World and who had already accompanied Martin Frobisher in his search for the Northwest Passage in the 1570s CE. White would paint the colony, wildlife and peoples of the region, creating an invaluable pictorial record which still survives today. Indeed, one might say that White created the only success of the entire expedition. Also on board were the returning natives, Manteo and Wanchese.

Things did not start well when a storm in mid-May separated the fleet and Grenville in the Tyger was blown off course to end up in Puerto Rico. A few small Spanish vessels and ports were then plundered in the Caribbean - as was always intended - in order to help pay for the expedition. Eventually regrouping and restocking at Hispaniola, three ships made their way tentatively through the difficult shallows of the Carolina Banks. In mid-July, the Tyger ran aground and seawater seeped into the ship's stores, ruining much of the foodstuffs meant for the colonists. The trio of ships was then joined by the remaining two vessels which had also got lost in the storm.

The all-male settlers were led by Ralph Lane (d. 1603 CE) and, unable to reach the mainland proper, they were deposited on Wokokan Island. Lane and Grenville did not get on and the colonists moved to the northern end of nearby Roanoke Island when the mariner sailed back to England for more supplies. Lane was left with the smallest vessel, the pinnace, with which he might explore the region. Initially, there was some trade between the settlers and the Roanoke Indians thanks to Manteo and Wanchese acting as intermediaries. The Indians also told them of what sounded like gold and copper deposits to the north. Using the pinnace, Lane led an exploration up to Chesapeake Bay.

Grenville, meanwhile, like most Elizabethan mariners, never turned down the chance of a little profit if the opportunity presented itself. Off Bermuda, he captured the 300-ton Santa Maria de San Vicente on his way home. The capture of sugar, ivory and spices would pay off all of the expedition's costs. The next summer Grenville returned to Virginia with new provisions for the colony but, unbeknown to the mariner, the impoverished Lane and his fellows had, on 19 June 1586 CE, already left and sailed back to England with Sir Francis Drake, fresh from one of his raids against the Spanish in the Caribbean. Grenville missed the party by only a few weeks. Grenville did leave 15 men and two years of supplies for them to hold out until new colonists might arrive but these men were never seen or heard of again.

1587 CE: The 'Lost Colony'

Despite the trials and tribulations of the first attempt at a settlement, interest was piqued by the returning colonists who showed off such novelties as tobacco and potatoes. Consequently, in 1587 CE a second colonizing expedition to Roanoke was organised, again masterminded by Raleigh. John White was to be the colony's governor, presiding over the 117 settlers. This time the group included families and so there were 89 men, 17 women, and 11 children. Each family or male would receive at least 500 acres of land given to them by the Crown (there was the assumption that this territory belonged to Elizabeth in the absence of any other European presence. Native rights were not considered). The plan was to choose a new site in the Chesapeake Bay area but as the crews of the expedition ships were rather more keen on privateering in the Caribbean than sailing up and down worthless waterways, the colonists were deposited back on Roanoke Island on 22 July 1587 CE. Naturally, the Roanoke Indians had not simply forgiven and forgotten Lane's raid on their village and the murder of their chief back in 1585 CE and so there was really no hope for these new settlers to establish a peaceful trading partnership. This became painfully obvious when one colonist, George Howe, was found dead on the beach on 28 July.

Legacy & Rumours

Thomas Hariot (1560-1621 CE), one of the 1585 CE colonists, wrote an account of his experiences in A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. This report was published in 1588 CE and, translated into French, German, and Latin, it did much to persuade officials that North America could be a source of wealth and not simply be used as a base from which to attack Spanish ships. The report also included 23 drawings by John White and so preserved for posterity this early view of Native Americans in the region, as well as providing navigational charts and records of local flora and fauna. Finally, the failure of the Roanoke Colony may have pushed Walter Raleigh to try exploration firsthand. The mariner's first expedition in search of El Dorado in South America in 1595 CE may have been motivated by the necessity to restore his position in Elizabeth's court.

English colonists would be back in North America, of course, first with the foundation of Jamestown in Virginia in 1607 CE and then the Pilgrims of the Mayflower, who established the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1620 CE. The Jamestown colonists did make an attempt to discover what happened to the Roanoke colonists in 1608 CE, and there were rumours amongst the Indians of a group of light-skinned and fair-haired people living to the south but nothing concrete ever came to light. One Jamestown colonist, William Strachey, reported in his 1612 CE History of Travel in Virginia Britannia that the Roanoke colonists had tried to establish a settlement at their original destination in the Chesapeake Bay area but they were killed by Indians there. Another rumour told of seven colonists surviving this massacre and then living with Indians further south but, again, no hard evidence was ever discovered, even if a local tribe, the Lumbee, do claim in their ancestral history that this is what happened to the last few members of the 'Lost Colony'. Finally, research by archaeologists in the region, conducted since 2010 CE over a ten year period, has uncovered artefacts which suggest the colonists integrated with the local indigenous tribes.