The government of the Byzantine Empire was headed and dominated by the emperor, but there were many other important officials who assisted in operating the finances, judiciary, military, and bureaucracy of a huge territory. Without elections, the ministers, senators, and councillors who governed the people largely acquired their position through imperial patronage or because of their status as large landowners. Government was multi-levelled based on the geographical division of the empire's population and although corruption, rebellions, and invasions threatened the functioning of the system, and even caused its reduction in scale, the system nevertheless survived for centuries to become one of the most sophisticated apparatus of government seen in any empire in history.

The Emperor

The Byzantine emperor (and sometimes empress) ruled as an absolute monarch and was the commander-in-chief of the army and head of the Church and government. He controlled the state finances, and he appointed or dismissed nobles at will, granting them wealth and lands or taking them away. The position was conventionally hereditary, but new dynasties were regularly founded as usurpers took the throne, usually military generals backed by the army. Unlike in the west, the Byzantine emperor was also head of the Church and so could appoint or dismiss the most important ecclesiastical role in the empire, the Patriarch or bishop of Constantinople. Further, the emperor was widely regarded as having been chosen by God to rule for the good of the people.

The emperor was distinguished by his magnificent royal residence, the Great Palace of Constantinople, and by his imperial regalia - the jewelled crown, belt, cloak, and brooch seen in so many depictions in Byzantine art. His or her image was widely seen as it appeared on coinage, official seals, weights, mosaics, and sculpture.

Given the size of the empire and the complexity of all the different facets of government necessary for it to run smoothly, the emperor was, by necessity, obliged to consult with a team of close advisors. Such members of an inner circle at court, the comitatus, need not have held any formal position, but there were other permanent offices and positions which helped disseminate the imperial will to all corners of the empire. There were, in addition, the court eunuch chamberlains (cubicularii) who served the emperor in various personal duties but who could also control access to him. Eunuchs also held positions of responsibility themselves, chief amongst these being the holder of the emperor's purse, the sakellarios whose powers would increase significantly from the 7th century CE.

The Senate & Imperial Ministers

The main forum of government was the Senate of Constantinople, which was made up of aristocratic males who were given their position by the emperor. Created by Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE), it was modelled on the Roman Senate. Although in practice the emperor could make any decision he wished, at least in theory he was supposed to consult the Senate and particularly the smaller group of the most senior senators known as the sacrum consistorium. This was especially so for matters of state importance - declarations of war, treaties of alliance, and so on. The Senate, therefore, was really only an advisory body. It could, though, function as the highest court in the land in rare cases of high treason. Leo VI (r. 886-912 CE) reduced the role of the Senate even further, but it would remain as an institution until the fall of the empire in the mid-15th century CE.

Key ministers who reported to the emperor but had some autonomy of authority included the following:

- the quaestor sacri palatii or chief legal officer and head of the judiciary

- the magister officiorum who looked after the general administration of the palace, the army and its supplies, the secret police, transport, and foreign affairs

- the cursus publicus who supervised the public post

- the comes sacrarum largitionum who controlled the state mint (Sakellion) and supervised customs houses, the state workshops and armouries, and the state's gold and silver mines. He collected some specific taxes, paid out extraordinary bonuses to the army, and supervised the distribution of clothing to the court.

- the comes rei privatae who looked after the imperial estates and the emperor's personal wealth

- the praepositus sacri cubiculi or chief eunuch who typically controlled who could have a personal audience with the emperor

- the Urban Prefect or Eparch who was, essentially, the mayor of Constantinople and had to run the city, manage its prisons, ensure public order was maintained, supervise building projects, and organise public spectacles.

The emperor and the above officials were supported by various ministries and their heads (domestikoi) such as the head of orphanages (orphanotrophos) and the head of public records (protasekretis), as well as countless minor officials (logothetes) and archivists (chartoularioi).

Regional Government

The Byzantine Empire was divided into the following territorial and administrative units:

- Prefectures (4)

- Dioceses (12)

- Provinces (100+)

- Town Councils

There were four prefectures, each governed by a Praetorian Prefect. The most important was the Praetorian of the East (the others governed Gaul, Italy and Illyricum) and, like his colleagues, he was responsible for all administrative, fiscal, and judicial affairs in his area. Prefects supervised and maintained the public post, roads, bridges, post-houses, and granaries in their area.

The prefectures were further divided into dioceses with their respective governors (vicarii) and each of these into administrative provinces, each with its own governor who supervised the individual city councils or curiae. Cities which were the seat of a governor such as Ephesus, Sardis and Aphrodisias, flourished as the governors sought to leave lasting monuments in their city and support the culture there. This was usually to the detriment of smaller towns in the province, and there are even records of emperors admonishing governors for dismantling monuments and stealing the stones in lesser towns in order to beautify the provincial capital.

Members of a curia were usually the wealthier local citizens, the land-owning elite (archontes), and although there were no elections, the ordinary people could voice their opinions at public events by acclaiming or booing public figures, just as factions of the crowd at the Hippodrome of Constantinople sometimes did towards the emperor. Public opinion might not bring the dismissal of councillors or other government officials but it could affect their chances of promotion as the emperor and central government were always on the watch for signs of public unrest in the provinces. Riots did occasionally break out, and the damage and economic disruption they caused was best avoided.

Local councillors were responsible for all public services and the collection of taxes in their town and its surrounding lands (curiously, any shortfall had to be made up by the councillors themselves until that onerous obligation was abolished in the early 6th century CE). This was a deliberate policy by emperors to separate tax revenue from anyone holding positions of military power and, therefore, reduce the possibility that a usurper could fund that portion of the army he commanded against the state. The main tax was a land tax called the annona, which was calculated in consideration of a census (indictio) taken every 5, and then later, 15 years.

Local councils also had to help with national services such as providing horses for the empire's postal system. The local councils could directly petition the emperor so that there was both a direct and indirect chain of authority through which imperial policy was transmitted to the ordinary people. Leo VI abolished the councils in the 9th century CE, and their duties were redistributed to other officials. Finally, to ensure that government policy was carried through in practice, there was a whole army of imperial inspectors who were regularly dispatched to the provinces.

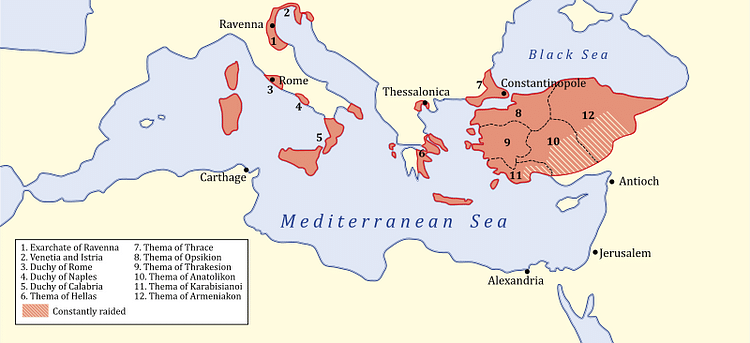

In the 7th century CE, as the empire shrank significantly and what remained became increasingly threatened by its neighbours. Emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE), or his immediate successors, permanently changed the system of central government so that governors of the newly created large provinces or themes (themata) were now, in effect, provincial military commanders (strategoi) with civil responsibilities who were directly responsible to and reported to the emperor himself. The system of Praetorian Prefects was, therefore, abolished, and the logothetes, those minor officials looked down upon previously, became more instrumental in the successful running of the government and civil administration.

Thus the whole bureaucracy was simplified and the number of officials massively reduced with the most important logothetes being:

- the logothetes tou stratiotikou who was in charge of military affairs from spending to armaments and supplies

- the logothetes tou genikou who was in charge of the land tax amongst many others

- the logothetes tou dromou who was in charge of foreign affairs, internal security, the public post, protection of the emperor, roads, and official public ceremonies.

In the 8th century CE, when armies of certain themes and strategoi posed a threat to the emperor's position, the themes were reorganised into smaller regional units to reduce their military power. By the 11th century CE, the theme system went into decline as emperors like Basil II (r. 976-1025 CE) preferred to rely on the greater loyalty of their own private army. The strategoi were gradually replaced by other officials with less overall powers such as the doux or katepano (military governor) and praitor (responsible for fiscal and judicial matters).