The Azuchi-Momoyama Period (Azuchi-Momoyama Jidai, aka Shokuho Period, 1568/73 - 1600 CE) was a brief but significant period of medieval Japan's history which saw the country unified after centuries of a weak central government and petty conflicts between hundreds of rival warlords. Oda Nobunaga (r. 1568-1582 CE) would establish himself as the military ruler of Japan, and his castle at Azuchi, east of Kyoto, gives the period the first half of its name. Nobunaga's successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi (r. 1582-1598 CE) would continue his work to unify all of Japan, and his base of Momoyama, south of Kyoto, provides the second half of the period's name. Hideyoshi came unstuck with his two failed invasions of Korea, and the period ended with the succession conflict that would see Tokugawa Ieyasu establish the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868 CE).

The Muromachi Period

The Muromachi Period (1333-1573 CE) had been one of turmoil for Japan with the Ashikaga shoguns never quite in control of all their provinces. The biggest crisis came with the Onin War (1467-1477 CE), a civil war which destroyed Heiankyo and created a century-long aftermath of bitter infighting between rival warlords. It would require one warlord to gain total supremacy for Japan to enjoy peace and a stable government again. Oda Nobunaga would turn out to be that man. Nobunaga had expanded his territory gradually throughout the 1550/60s CE from his base at Nagoya Castle in Owari Province, central Japan, as he defeated all comers through a mix of sieges, battles, and diplomacy. He finally seized the capital Heiankyo in 1568 CE and then exiled the last Ashikaga shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, in 1573 CE. With these two actions, the Azuchi-Momoyama Period begins (hence some scholars choose 1568 CE as the start date while others plum for 1573 CE).

Oda Nobunaga

In 1579 CE and now in control of all central Japan, Oda Nobunaga established a new headquarters at the magnificent Azuchi castle outside the capital on the edge of Lake Biwa, hence this period of history's first name. Nothing remains today of the castle except its stone base, but it was the first to combine a plush residency with defensive features and have the huge multi-storey castle keep that became the norm in Japanese medieval castles. Unfortunately, Azuchi castle was burnt down in 1582 CE but was later rebuilt.

Nobunaga was able to defeat and maintain his position above rival warlords and to continue to expand his territorial control thanks to his large army which was well-equipped and which included the gifted general Toyotomi Hideyoshi (who would become Nobunaga's successor). Nobunaga was an innovator as he was one of the first Japanese leaders to adopt firearms, his armies having a corps of 3,000 musketeers who, in battle, fired in rotating ranks to create a continuous and devastating volley of fire. Nobunaga's army was also the first to have each man, including the infantry, issued with a full suit of armour. The territories Nobunaga gained were given to his loyal commanders to govern, and the lands of captured warlords were frequently redistributed and relocated to break old ties of loyalty.

In order to secure his grip on power, Nobunaga attempted to reduce the income of his rival daimyo (feudal lords) by abolishing the tolls on all roads. He boosted his own coffers by minting the first Japanese currency since 958 CE and standardising the exchange rates between all the different coins then in use. Another lucrative source of cash was to release merchants from their guilds and have them pay the state a fee instead. From 1571 CE an extensive land survey was begun to make the tax system more efficient. Another policy was to confiscate all weapons held by the peasantry from 1576 CE onwards, the so-called 'sword hunts', something his successors would also do. Meanwhile, Nobunaga continued to expand his territory, his goal was nothing less than a unified Japan. Not for nothing did the warlord emblazon on his personal seal 'Tenka Fubu' or 'a Unified Realm under Military Rule.'

It was not just rival lords who suffered under Nobunaga's ambition, many Buddhist temples - rich and powerful institutions at the time, several of which could field small armies - were attacked, too. The most infamous example of this policy was his destruction of the Enryakuji monastic complex on the sacred Mt. Hiei near Kyoto in 1571 CE. 25,000 men, women, and children were butchered in the attack. In contrast, Nobunaga encouraged the work of Christian missionaries in Japan as he saw the benefit of European contacts which brought trade and technology such as the firearms he put to such devastating use. The decline of the Buddhist temples also had repercussions in Japanese art with paintings, screens, sculptures and architectural decorations like door panels now becoming more secular in their subject matter - birds, flowers, and people doing everyday tasks were especially popular - and a great deal more flashy with bold colours and gilding aplenty.

On 21 June 1582 CE Nobunaga, a man with innumerable enemies, was betrayed by one of his vassal allies, Akechi Mitsuhide. In an episode known as the Honnoji Incident, Mitsuhide, for reasons unknown, successfully attacked Nobunaga's position and, according to one version of the story, when it became clear that his capture was imminent, the man who then controlled half of Japan committed suicide. In a different version, the warlord died in flames as the temple burnt down. Nobunaga's son and chosen heir, Nobutada, died in the same disaster.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Nobunaga's death would be avenged swiftly when his foremost general Totoyomi Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide at the Battle of Yamazaki and declared himself Nobunaga's successor. Hideyoshi would rule Japan from 1582 to 1598 CE. Hideyoshi's choice of base at his Momoyama castle ('Peach Mountain') in Fushimi, south of Heiankyo, would give the period the second half of its name. Castles, which had sprung up everywhere in the troubled times of the preceding Muromachi Period, were now clearly more for show than defence, although many had impressive wide moats and the introduction of firearms to Japan did necessitate a greater use of stone, thicker walls and windows for musketeers (often triangular) just in case a castle were ever attacked. However, as with the famous Himeji Castle (1581-1609 CE), most castles were never actually attacked. Many castles, too, continued to create ever-widening settlements around them and some of these castle towns would eventually become major cities like Edo (Tokyo) and Osaka.

Hideyoshi commanded a force of some 200,000 men and, like his predecessor, he successfully combined military campaigns with diplomacy amongst his rival daimyo to establish himself as the ruler of most of Japan in 1590 CE. In a five-year period beginning in 1585 CE, Hideyoshi had attacked western Japan, Kyushu, and Shikoku. As with other military leaders, Hideyoshi still sought legitimacy from the monarchy. To gain royal favour from the emperor (who had no real power of his own), he gave money for court ceremonies and rebuilt the palace at the capital. Hideyoshi ultimately awarded himself the title of Taiko ('retired regent').

Hideyoshi is noted for his policies and reforms when he governed Japan. To fund the state he extracted taxes from the peasantry and the commercial activities in larger cities. In 1591 CE Hideyoshi developed a rigid class system with different levels for a warrior (shi), farmer (no), artisan (ko), and merchant (sho), the often-called shi-no-ko-sho system. Each class was given an importance based on its production value, and no movement between the levels was permitted, meaning that, for example, only a young man born into a samurai family could become a samurai. Another consequence was that samurai could not be both warriors and part-time farmers as they had been in the past and so now they had to choose one way of life over the other, making them wholly dependent for their pay on their lord if they did choose to serve as samurai. The system, although a little confused in practice and certainly not rigidly imposed everywhere, would remain in place right through the Edo Period (1603-1868 CE).

In 1587 CE Hideyoshi passed an edict to expel all Christian missionaries from Japan but it was only half-heartedly enforced. Concerned that the Jesuits were encouraging the persecution of Buddhist and Shinto believers and that Portuguese traders were selling Japanese as slaves, another edict was passed in 1597 CE. This time a more serious intent was established with the mutilation and execution by crucifixion of 26 Christians in Nagasaki which included priests who had defied the first edict. Still, after this brutal beginning, the campaign to rid Japan of this foreign religion was largely abandoned as impractical and, in any case, Hideyoshi did not want to jeopardise the lucrative silk-for-silver trade with Portuguese-controlled Macao. The Japanese leader's preoccupation with trade is evidenced in his determined campaign to wipe out the wako pirates that plagued East Asian seas. Putting them to his own use, Hideyoshi permitted pirate ships to legitimately trade, provided they carried his own personal red seal, hence their common name of shuin-sen or 'red seal ships.'

The Japanese Invasion of Korea

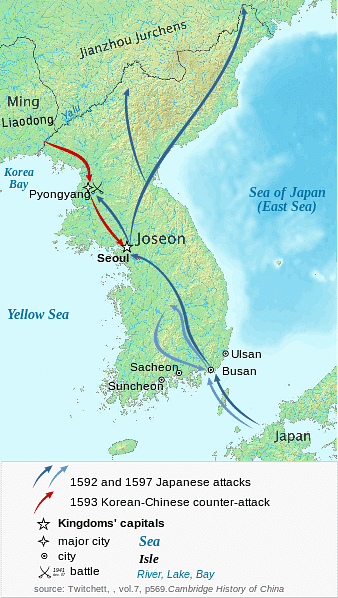

Such was his total grip on Japan, Hideyoshi began to look elsewhere for military action. Between 1592 and 1598 CE Hideyoshi would twice invade Korea in a conflict known as the Imjin Wars. The attack was meant to pave the way for an invasion of China, then ruled by the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE), and this hugely ambitious plan has led some to consider Hideyoshi deranged.

Whatever his motives and mental state, Hideyoshi certainly displayed his renowned planning and logistics skills as a fleet carrying 158,000 men landed in Korea at Busan (Pusan) and got off to a flying start. Cities like Pyongyang and Seoul were captured as the Koreans were caught entirely by surprise and King Seonjo (r. 1567-1608 CE) fled to the north of his country. The Japanese advantage in possessing firearms was another telling factor in the success.

Eventually, though, the combined operations of the Korean navy led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin (l. 1545-1598 CE) which had covered-deck 'turtle-ships' (kobukson) armed with cannons, a large land army from Ming China, and well-organised local rebels resulted in the first invasion stalling in 1593 CE as the Japanese could not resupply their northern armies. The Japanese did remain in occupation of the south of the peninsula.

After protracted and unsuccessful peace talks, Hideyoshi launched a second, much less successful invasion in 1597 CE, and when the warlord died the next year, the Japanese forces withdrew from the peninsula. One of the largest military operations ever undertaken in East Asia prior to the 20th century CE, the conflict would not only have devastating consequences for all concerned in terms of loss of life and the depredation of agriculture and culturally important properties but permanently sour relations between Japan and Korea. The war had also cost the Ming Dynasty a fortune and contributed to its ultimate decline.

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Hideyoshi died of natural causes on 18 September 1598 CE, but he had already arranged for five senior ministers (tairo) to share the role of regent for his young son. These men, though, only fought amongst themselves for supremacy. One of these was Tokugawa Ieyasu (r. 1603-1605 CE) of the Matsudaira family, who had already unsuccessfully challenged Hideyoshi way back in 1584 CE. Ieyasu would eventually establish himself as military supremo after winning the 1600 CE Battle of Skeigahara against those generals who supported Hideyoshi's son. Ieyasu took the title of shogun in 1603 CE and thus established the Tokugawa Shogunate which finally saw the complete unification of Japan and which then enjoyed some 250 years of peace. As the old Japanese saying goes, "Nobunaga mixed the cake, Hideyoshi baked it, and Ieyasu ate it" (Beasley, 117). This next period of Japanese history would be known as the Edo Period after the capital was moved to that city, now known as Tokyo.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.