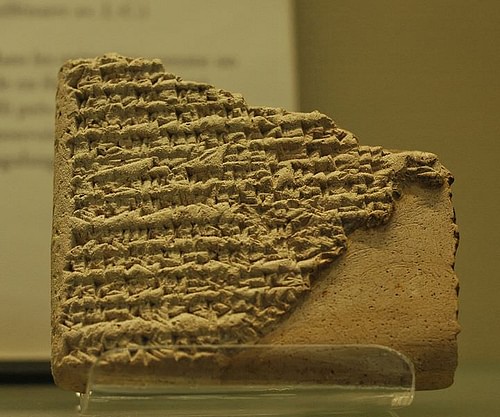

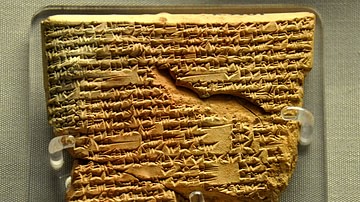

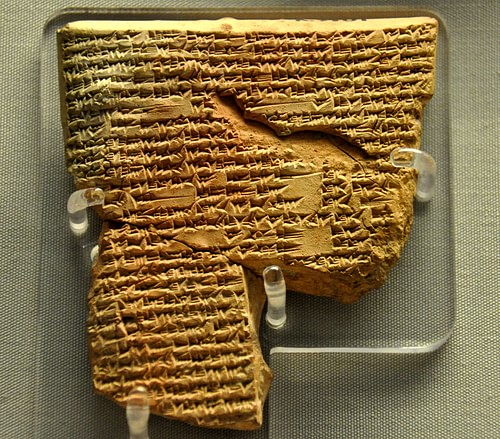

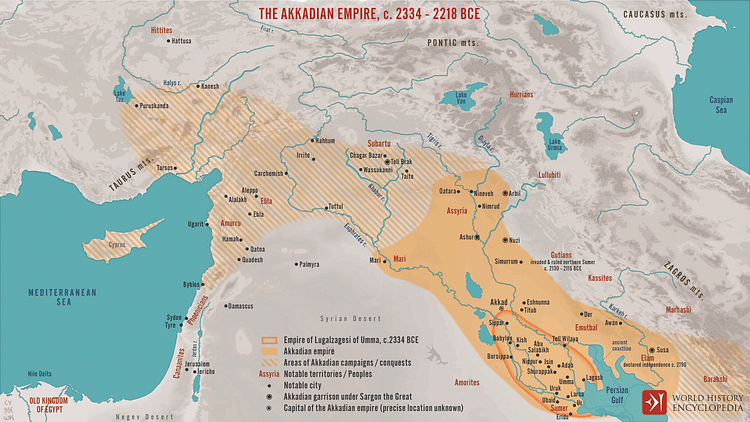

The Legend of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2300 BCE) is an Akkadian work from Mesopotamia understood as the autobiography of Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE), founder of the Akkadian Empire. The earliest copy is dated to the 7th century BCE and was found in the ruins of the Library of Ashurbanipal in the 19th century.

The text, most likely composed c. 2300 BCE, and also known as The Birth Legend of Sargon, describes the king's humble origins and rise to power with the help of the goddess Ishtar and concludes with a challenge to future kings to go where he has gone and do as he has done. Sargon was the founder of the first multinational empire in the world whose reign became legendary, inspiring many tales about him, but very little is known of his life apart from works such as The Legend of Sargon of Akkad and the literary piece Sargon and Ur-Zababa.

Both pieces today are sometimes classified as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian naru literature – the world's first historical fiction – in which a famous figure, usually a king, is featured as the main character in a fictional work. This genre appeared around the 2nd millennium BCE and was quite popular, as evidenced by the number of copies found of naru works.

The purpose of naru literature was not to deceive an audience but to impress upon them some important religious or cultural value. In the case of The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, however, the naru genre seems to have been used to establish Sargon as a 'man of the people' who, beginning life as an orphan with nothing, forged his own destiny and established an empire.

The Legend & Naru Literature

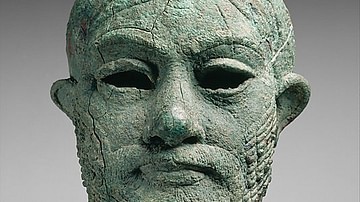

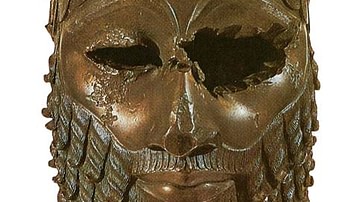

Sargon of Akkad was keenly aware of his times and the people he would rule over. He seems to have understood, early on, that the common people resented the nobility and, while he was clearly a brilliant military leader, it was the story he told of his youth and rise to power that exerted a powerful influence over the Sumerians he sought to conquer.

Instead of representing himself as a man chosen by the gods to rule, he presented a more modest image of himself as an orphan set adrift in life who was taken in by a kind gardener and granted the love of the goddess Inanna/Ishtar. According to The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, he was born the illegitimate son of a "changeling", which could refer to a temple priestess of Ishtar (whose clergy were androgynous) and never knew his father.

His mother could not reveal her pregnancy or keep the child, and so she placed him in a basket which she then set adrift on the Euphrates River. She had sealed the basket with tar, and the water carried him safely to where he was later found by a man named Akki, a gardener for Ur-Zababa, the king of the Sumerian city of Kish. In creating this legend, Sargon carefully distanced himself from the kings of the past (who claimed divine right) and aligned himself with the common people of the region rather than the ruling elite.

The Legend, as noted, is considered by some scholars today as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian naru literature, but it is unknown whether it would have been understood that way in its time. Scholar O. R. Gurney defines the genre and its origin:

A naru was an engraved stele, on which a king would record the events of his reign; the characteristic features of such an inscription are a formal self-introduction of the writer by his name and titles, a narrative in the first person, and an epilogue usually consisting of curses upon any person who might in the future deface the monument and blessings upon those who should honour it. The so-called "naru literature" consists of a small group of apocryphal naru-inscriptions, composed probably in the early second millennium B.C., but in the name of famous kings of a bygone age. A well-known example is the Legend of Sargon of Akkad. In these works, the form of the naru is retained, but the matter is legendary or even fictitious. (93)

The extant copy, made long after Sargon's death, conveys the story Sargon would have presented regarding his birth, upbringing, and reign. Naru pieces such as The Legend of Cutha or The Curse of Agade use a well-known historical figure (in both these cases Naram-Sin, Sargon's grandson) to make a point concerning the proper relationship between a human being (especially a king) and the gods. Other naru literature, such as The Great Revolt and The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, tell a tale of a great king's military victory or origin. In Sargon's case, it would have been to his benefit, as an aspiring conqueror and empire builder, to claim for himself a humble birth and modest upbringing.

Purpose & Text

At the time Sargon came to power in 2334 BCE, Sumer was a region which had only recently been united during the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) under Eannatum, King of Lagash, and even then, it was not a cohesive union. Prior to Eannatum's conquest, Sumerian cities were frequently at war with each other, vying for resources such as water and land rights, a common cause of Mesopotamian warfare. Further complicating the situation was the discrepancy between the rich and the poor. Scholar Susan Wise Bauer writes on this, commenting:

Sargon's relatively speedy conquest of the entire Mesopotamian plain is startling, given the inability of Sumerian kings to control any area much larger than two or three cities [but the Sumerians] were suffering from an increased gap between elite leadership and poor laborers. [The rich] used their combined religious and secular power to claim as much as three-quarters of the land in any given city for themselves. Sargon's relatively easy conquest of the area (not to mention his constant carping on his own non-aristocratic background) may reveal a successful appeal to the downtrodden members of Sumerian society to come over to his side. (99)

By presenting himself as a 'man of the people', he was able to garner support for his cause and took Sumer with relative ease. Once the south of Mesopotamia was under his control, he then went on to create the first multinational empire in history. That his reign was not always popular, once he was securely in power, is attested to by the number of revolts he was forced to deal with as described in his inscriptions. Early on, however, his appeal would have been great to people who were tired of the wealthy living as they pleased at the expense of the working lower class.

The social hierarchy in Sumer was rigid, with only a very few enjoying lives of leisure and the majority doing all the work that allowed the cities to function. In this kind of social situation, a contender for rule who was the child of a single mother, abandoned, and taken in by a gardener, would have won the approval of the people far more than any of the elite who then ruled the cities.

The following translation of the Legend comes from J. B. Pritchard's The Ancient Near East, Volume I, pages 85-86:

Sargon, the mighty king, king of Agade, am I.

My mother was a changeling, my father I knew not.

The brother(s) of my father loved the hills.

My city is Azupiranu, which is situated on the banks of the Euphrates.

My changeling mother conceived me, in secret she bore me.

She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen she sealed

My lid.

She cast me into the river which rose not (over) me,

The river bore me up and carried me to Akki, the

drawer of water.

Akki, the drawer of water lifted me out as he dipped his

e[w]er.

Akki, the drawer of water, [took me] as his son

(and) reared me.

Akki, the drawer of water, appointed me as his gardener,

While I was a gardener, Ishtar granted me (her) love,

And for four and [ ... ] years I exercised kingship,

The black-headed [people] I ruled, I gov[erned];

Mighty [moun]tains with chip-axes of bronze I con-

quered,

The upper ranges I scaled,

The lower ranges I [trav]ersed,

The sea [lan]ds three times I circled.

Dilmun my [hand] cap[tured],

[To] the great Der I [went up], I [...],

[...] I altered and [...].

Whatever king may come up after me,

[...]

Let him r[ule, let him govern] the black-headed

[peo]ple;

[Let him conquer] mighty [mountains] with chip-axe[s

of bronze],

[Let] him scale the upper ranges,

[Let him traverse the lower ranges],

Let him circle the sea [lan]ds three times!

[Dilmun let his hand capture],

Let him go up [to] the great Der and [...]!

[...] from my city, Aga[de ... ]

[...] ... [...].

Commentary

The great king is carefully presented in the first twelve lines as the child cast off by his mother, who finds a home with Akki the gardener, and is loved by the goddess Ishtar. Once Ishtar and her favor is established in line 12, the narrator moves instantly to "And for four years I exercised kingship" in line 13 and then devotes the rest of the piece to his military exploits and legacy.

This progression of the story would have inspired the people of ancient Mesopotamia in much the same way that a "poor boy makes good" tale does in the present day. Sargon not only boasted about what he was able to accomplish as king but also told the people of his very humble beginnings and how it was through the kindness of a stranger and the grace of a goddess that he was able to achieve his great triumphs.

There is no way of knowing whether any of what Sargon says about his early life in the inscription is true; that is precisely the point of it. Whoever Sargon was, and wherever he came from, is obscured by the legend – which is the only known work giving his biography. "Sargon" is not even his actual name, but a throne name he chose for himself, which means "Legitimate King", and although inscriptions and his name would indicate he was a Semite, there is no way of knowing even that for certain.

He claims his home city is Azupiranu, but such a city is mentioned in no other extant texts and is thought to never have existed. Azupiranu means "city of saffron" and, since saffron was a valuable commodity in healing as well as in other applications, he was perhaps simply linking himself to the concept of value or worth. The repetition of the image of Sargon being rescued from the river by a "drawer of water" would also have had symbolic resonance for an ancient Mesopotamian audience, in that water was considered a transformative agent as well as how one was cleared of any wrongdoing.

The means by which a person accused of a crime was found guilty or innocent was known as the ordeal, in which the accused was thrown into the river or leaped in, and if they survived, they were innocent; if not, the gods, through the agency of the river, had delivered a verdict of guilt. Further, the afterlife in Mesopotamian belief was separated from the land of the living by a river, and the deceased left their earthly life behind as they crossed over.

His journey, then, from his home city, via the Euphrates River, to his destiny with the "drawer of water" would have symbolized transformation and also his worthiness, in that he had survived his own ordeal as an infant. The legend replaced whatever biographical truth there may have been and, in time, became the truth. This seems to have been the effect of much of the naru literature: the myth, in time, became the reality. Regarding this, the scholar Gerdien Jonker writes:

It should be made clear that the ancient writers were not aiming to deceive with their literary creations. The literature inspired by the naru formed an excellent medium with which, by departing from traditional forms, a new social "image" of the past could be created. (95)

Even so, the above is a modern interpretation of the ancient texts; it is unknown how the works now classified as Mesopotamian naru literature were understood by the people of the time. It seems probable that the original audience would not have questioned the story of a child abandoned by his mother in the river who floated downstream to be found by a gardener, was granted the love of a goddess, and rose to become the most powerful man in Mesopotamia through her grace and his own character. As there was no conflicting story to compare it to, it would have been accepted as an accurate account of his life and, in the modern era, at least the version he wanted future generations to remember.

The Legend is recognized by modern scholars, including Paul Kriwaczek, as the inspiration for the tale of Moses' origin in the biblical Book of Exodus, which went unchallenged until the present era. Many people around the world today accept the story of Moses and the bullrushes and the Egyptian Princess as truth, and this is how Sargon's legend would have been received by the people of ancient Mesopotamia. Whoever he may actually have been, it certainly did not hurt his cause to be known as the orphaned son of a priestess instead of a privileged heir to a throne.

Conclusion

The text was discovered in the ruins of the Assyrian city of Nineveh c. 1850-1853 by the archeologists Hormuzd Rassam and Sir Austen Henry Layard who were excavating the site (though some attribute the find to Sir Henry Rawlinson, who worked with Layard). Hormuzd and Layard are famous for many important discoveries throughout Mesopotamia but perhaps most for uncovering the Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. The Legend of Sargon of Akkad was part of that library and this, of course, suggests the story was still being read in the 7th century BCE, almost 2,000 years after Sargon's reign.

By that time, Sargon was already legendary. The kings of the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE), notably Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) and Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE), associated themselves with Sargon and his successors as more benign versions of the Akkadian kings. Hammurabi of Babylon (r. 1792-1750 BCE) also seems to have drawn on Sargon's model, especially in the organization of his military, and the Assyrian kings did the same. By the time of Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE), Sargon's name would have been as well-known as those of Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar are today.

Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE) sent his emissaries throughout Mesopotamia collecting and copying all the works they could find for his library to preserve the past "for distant days" when they would be read by future generations. Among the over 30,000 cuneiform texts discovered in the ruins of the library, Sargon's autobiography, whether truth or fiction, presents one of the earliest, if not the earliest, rags-to-riches tales in world history and continues to fascinate and inspire audiences in the present day just as it was meant to do when first written.