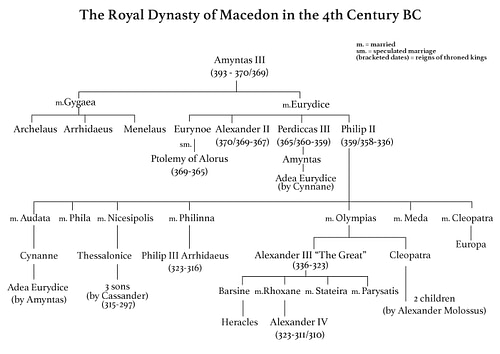

Olympias (c. 375-316 BCE) was the second wife of Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) and the mother of Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE). Olympias was the driving force behind Alexander's rise to the throne and was accused of having a hand in the assassination of Philip by Pausanias of Oretis. After Alexander's death, she fought for her grandson but was defeated by Cassander (r. 305-297 BCE).

Early Life & Marriage to Philip

Olympias, whose birth name was actually Myrtale, was the daughter of Neoptolemus, the late king of Epirus, a kingdom to the southwest of Macedonia. Her ancestors, the Molossians, claimed to be descended from Molossus, the son of Andromache and Neoptolemus – a son of Achilles – who had slain King Priam of Troy during the Trojan War.

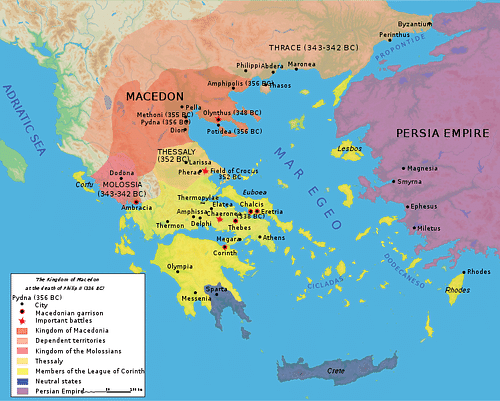

While historians disagree on how Philip and Olympias met, the most widely accepted story is written that they met on Samothrace, an island in the Aegean Sea lying between Macedonia and Troy. The island was noted as the religious centre of the twin gods Caberi. While Philip may have participated in the religious ceremonies, he was actually there to promote an alliance. When he saw the young Olympias, a red-haired woman with intoxicating beauty and a fiery temper, it was love at first sight. Plutarch wrote:

…after Philip has been initiated on Samothrace along with Olympias, he fell passionately in love with her, and although he was only a young adult and she was an orphan, he went right ahead and betrothed himself to her… (Alexander, 2.1)

It was not uncommon for a king to marry more than once, and in Philip's case, many of his marriages were solely for the purpose of making alliances. It was this way with Olympias, for she would be his second wife. In 357 BCE, they married; Olympias was about 18 at the time and Philip about 28. Historians have discussed the many omens that surrounded the young couple's wedding night. In his Greek Lives Plutarch wrote:

On the night before they were to be locked into the bridal chamber together, the bride had a dream in which, following a clap of thunder, her womb was struck by a thunderbolt, this started a vigorous fire which then burst into flames and spread all over the place before dying down. (Alexander, 2.2)

Together with Philip's dream where "… he was pressing a seal on his wife's womb, and that the emblem on the seal was the figure of a lion…" the future of their great son was foretold (Alexander, 2.2). Philip and Olympias had two children, Alexander and a daughter, Cleopatra, but after Philip saw his wife sleeping with snakes, his days of visiting her bedchamber were over. Olympias had long been a devotee to the cult of Dionysos, something that angered many of the Macedonian people and she may even have introduced the practice of handling snakes to the cult.

Birth of Alexander

On July 20, 356 BCE Olympias proved her value to Philip by providing him with an heir in Alexander. Without an heir, she would only have been beneficial to Philip and Macedonia as an alliance with Epirus. In actuality, there was another possible heir to the throne, a younger half-brother, Phillip Arridaeus, whose mother was a commoner, named Philinna. However, according to Plutarch the always jealous Olympias poisoned him with a drug that eventually addled his wits so he would never be a threat to Alexander becoming king.

Three major events occurred in the life of Philip on the day of the future king's birth. At the time of Alexander's birth, Philip was away in battle at Potidaea. On this day he received the good news that one of his commanders, Parmenio, had won a decisive battle against the Illyrians. Secondly, his racehorse had won at the Olympic Games (this is where Myrtale became Olympias), and lastly, his son and heir was born. A soothsayer would later claim that Alexander's birth, coinciding with the other events, meant the young boy would grow to be invincible.

After Alexander's arrival, his mother's primary objective in life was to make him king. Olympias doted on the young Alexander, telling him constantly of his noble lineage and his ties to Achilles. This story had a powerful effect on Alexander (he even carried a copy of the Iliad with him). When he crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor, one of the first places he visited was the remains of Troy, paying homage to his ancestor Achilles. To see to his early education, Olympias brought in a relative, the stern Leonidas of Epirus, to act as both a tutor and mentor to the future king. Afterwards, Aristotle would be summoned from Athens to complete his education.

Divorce

A situation soon arose that could threaten Olympias and her quest to enthrone her son - Philip's marriage to Attalus's niece, Cleopatra-Eurydice. According to those around Philip, Alexander was only half Macedonian, and the pressure was on for the king to marry someone of pure blood. So, Philip divorced Olympias, accusing her of adultery, and even claiming that Alexander was not his son. Philip's marriage to Cleopatra-Eurydice combined with her pregnancy put Olympias in a precarious situation. If the baby were a boy and, therefore, a legitimate heir to the throne, Alexander would not become king. This was further complicated when Olympia's brother, Alexander, who Philip had put on the throne of Epirus, was betrothed to her daughter (and his niece), Cleopatra. With this marriage, she would no longer serve a purpose even as a diplomatic tie to Epirus.

At the wedding banquet of Phillip and Cleopatra-Eurydice, Attalus (one of Philip's commanders) made a disparaging remark about Alexander, calling him a bastard. After this verbal assault, Alexander angrily rose to his feet, deriding his drunken father's inability to cross the room. Plutarch wrote:

Philip got up to attack Alexander and drew his sword but luckily for both of them his anger and the wine he had drunk made him stumble and fall…After this drunken brawl Alexander took Olympias and set her up in Epirus, while he stayed among the Illyrians. (Alexander, 9.5)

Possibly, Olympias' purpose of returning to Epirus was not only to get her away from the wrath of Phillip but also to coax her brother into declaring war on Philip. After Philip arranged reconciliation through Demaratus of Corinth, Alexander and Olympias were allowed to return to Pella.

Death of Philip & Rise of Alexander

In 336 BCE, at the wedding banquet of Olympias' brother Alexander to her daughter Cleopatra, Philip was assassinated by the disgruntled Pausanias of Oretis, who had been rebuked by Philip after he had asked for retribution against Attalus. Suspicion immediately fell upon Olympias who some believed had encouraged Pausanias to seek revenge and kill Philip. Plutarch wrote:

When Pausanias, who had been assaulted at the instigation of Attalus and Cleopatra, murdered Philip for failing to recompense him, most of the blame attached itself to Olympias, on the grounds that she had encouraged the young man in his anger and incited him to do the deed … (Alexander, 10.4)

There is even some evidence that she had horses waiting for the assassin to use for his escape. After Philip's death and Alexander's ascension to the throne, Cleopatra-Eurydice and her young daughter (there may also have been a son) were put to death on Olympias' orders - some claim they were burned to death while others say Cleopatra was forced to hang herself. With this done, Olympia's future was secure - she was the king's mother.

![Alexander the Great [Profile View]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/1047.jpg?v=1660133770)

When Alexander prepared to cross the Hellespont and into Asia Minor, his mother pulled him aside and told him that his true father was not Philip but Zeus; therefore, he must act with courage, something suitable to his divine origin. He would never see his homeland or mother again. Throughout his travels across Asia, he and his mother corresponded often - she offered advice and he ignored it. Left behind to rule Macedonia and Greece was Antipater. Letters between Alexander and Antipater as well as those between Alexander and Olympias were filled with complaints and accusations; Antipater called her, among other things, a shrew while she said he was more like a king than a governor. In order to solve the quarrel, Alexander sent for Antipater to meet him in Babylon (some say it was just to get him away from Olympias), but Antipater sent his son Cassander in his place, something that angered Alexander.

After the Death of Alexander

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE and the onset of the Wars of the Diadochi, Olympias called for Roxanne, Alexander's wife, to come to Pella where she and her son the future Alexander IV would be safe. After Antipater's death in 319 BCE, one of Alexander's commanders Polyperchon was named the new regent; however, he was forced out by Cassander, fleeing to Epirus with Roxanne and the young Alexander.

While she had originally tried to remain neutral, Olympias realized her grandson could never be king as long as Cassander was regent, so she joined forces with her cousin Aeacides (King of Epirus) and the remainder of Polyperchon's army and invaded Macedonia. At the orders of Olympias, Alexander's half-brother Phillip (who actually had been king but in name only), his wife Eurydice and hundreds of selected Macedonians loyal to Cassander were executed in 317 BCE. However, Olympias' invasion failed; Cassander captured her at Pydna, and while he initially promised to save her life, he changed his mind and put her to death in 316 BCE. Sadly, Olympias' dream of her grandson inheriting the throne of Alexander would never be realized, and Roxanne and the young Alexander IV would meet the same fate as Olympias in 310 BCE.

![Olympia Provisions: Cured Meats and Tales from an American Charcuterie [A Cookbook]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/511I1-z40IL._SL160_.jpg)